mev crypto

What Is Miner Extractable Value (MEV)?

Miner Extractable Value (MEV) refers to the profits that can be earned by controlling the ordering of transactions—essentially, “who gets to check out first.” Imagine a blockchain as a supermarket checkout line: the order in which customers are served impacts the price and experience for each. Whoever controls the checkout can rearrange the line to collect higher tips or profit from price differences.

On blockchains, transactions first enter the “mempool,” a public waiting area visible to everyone. The party able to produce a block (since Ethereum’s Merge, this is the validator) or their collaborators can change the order of transactions in the mempool or insert their own, capturing arbitrage, liquidation rewards, and other additional profits. All such opportunities are collectively known as MEV.

Why Does Miner Extractable Value (MEV) Occur?

MEV arises from the combination of “public transaction flows” and “deterministic rules.” On one hand, the mempool makes all pending transactions visible. On the other, decentralized exchanges’ automated market maker formulas and lending protocol liquidation thresholds are open and predictable, which creates exploitable opportunities.

When a large trade hits an AMM, it moves the price significantly, affecting subsequent transactions. Whoever can insert their order at a key position can capture arbitrage. Similarly, if collateral in a lending protocol falls below a threshold, anyone can trigger liquidation and claim a reward, fueling competition for transaction ordering rights.

What Are Common Types of MEV?

Common types of MEV can be illustrated with real-world analogies:

-

Front-running/Back-running & Sandwich Attacks: If someone is about to buy tokens with 100 ETH, pushing up the price, an attacker can buy first (front-run), then after the large trade is executed, sell (back-run), sandwiching the victim’s transaction and profiting from the price difference.

-

Liquidation Capture: When a user’s collateral in a lending protocol drops below the required ratio, anyone can initiate liquidation and receive a reward. Searchers compete to place their liquidation transaction in the optimal position.

-

Cross-Pool Arbitrage: If a token’s price differs between two DEXs, a searcher constructs transactions to buy in the cheaper pool and sell in the more expensive one, arranging both trades adjacently in the block to secure risk-free or low-risk arbitrage.

-

NFT Minting & Whitelisting: In popular NFT launches with limited supply—like ticket sales—the earliest transactions get the spots. Ordering and gas fee bidding create significant MEV opportunities here.

All these types rely on mempool transparency and predictable protocol rules. As long as someone can influence transaction order, MEV is possible.

How Has MEV Changed After Ethereum’s Merge?

After Ethereum’s Merge, block production shifted from miners to validators, so “Maximum Extractable Value” is now more commonly used. The community has promoted “Proposer-Builder Separation” (PBS), where professional “block builders” assemble the most valuable blocks, and validators propose them.

Bridging these roles introduced relay and auction frameworks (such as MEV-Boost): searchers bundle opportunities and submit them to builders; builders bid to deliver the most valuable block to validators. This reduces single-point power but introduces reliance on relays and potential censorship risks.

How Is MEV Executed?

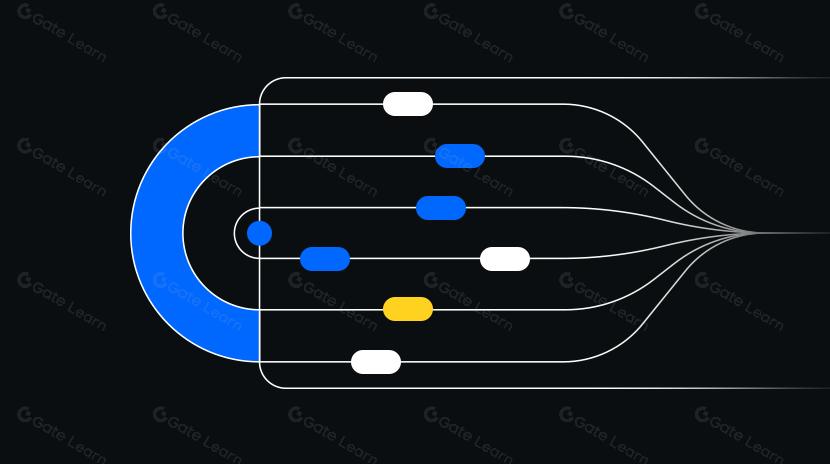

MEV extraction follows a process involving three new roles and two key concepts:

-

Roles: Searchers identify opportunities and construct transaction sequences; block builders assemble these sequences into blocks; validators have final authority to propose blocks and receive tips.

-

Concepts: The mempool is a public set of pending transactions; “transaction bundles” are sets of transactions executed in a specific order, often submitted privately to prevent interception.

Step 1: Searchers monitor the mempool for arbitrage, liquidation, or minting opportunities and simulate different orderings locally for maximum profit.

Step 2: Searchers package their own and target transactions into bundles, specifying maximum tips or revenue sharing.

Step 3: Bundles are sent to builders or relays to participate in auctions—higher bidders are more likely to be selected.

Step 4: Validators propose blocks including winning bundles; profits are split among searchers, builders, and validators as agreed.

How Can Regular Users Reduce MEV Risk?

To reduce MEV risks, users should minimize information leakage and slippage exposure while avoiding peak congestion times.

- Set low slippage tolerance and reasonable gas limits to avoid sandwich attacks. Prefer limit orders or protected routes via aggregators.

- Use wallets/RPCs or transaction channels supporting private submissions to bypass public mempools, lowering frontrunning risk.

- Consider intent-based matching services that aggregate user intents off-chain for optimal execution before posting a single on-chain transaction—reducing exposure.

- Break large swaps into multiple smaller trades at different times, especially during periods of high volatility, reducing market impact.

- Use stable, high-liquidity routes to minimize slippage; exercise caution with illiquid pools or newly launched tokens.

- In lending, maintain healthy collateral ratios and set alerts to avoid forced liquidations and associated MEV costs.

Note: Centralized exchanges like Gate use order-matching engines and order books—transactions do not pass through public mempools and are not subject to on-chain ordering-based MEV. However, on-chain transfers and DeFi interactions still require MEV risk awareness.

How Is MEV Different From Regular Arbitrage?

The key distinction is whether one can influence transaction ordering. Regular arbitrage is like transporting goods between stores—profiting from price differences without controlling the checkout line. MEV typically requires directly influencing transaction sequence (either directly or via cooperation with block builders) to guarantee profit.

There is overlap: cross-pool arbitrage under open competition resembles regular arbitrage, but when it requires bundling adjacent trades and paying builders for guaranteed ordering, it becomes MEV. Compliance and ethical debates focus on this point—certain MEV behaviors can harm user experience even if they do not violate protocol rules.

What Is the Impact of MEV on the Ecosystem?

For users, MEV means higher slippage, failed transactions, and unpredictable confirmation times—especially during popular token launches, NFT minting, or liquidation spikes.

For protocols, arbitrage-driven MEV helps synchronize prices across pools for more efficient pricing. However, sandwich attacks degrade user experience, prompting protocols and wallets to add protections like batch auctions, auction-based routing, or private submission mechanisms.

At the network layer, MEV has driven structural solutions like PBS that reduce some centralization risks but introduce new dependencies on relays and censorship risks. Gas bidding also amplifies externalities during congestion.

What Are Future Trends in MEV?

MEV governance is evolving along three main lines:

- Protocol Layer: The community is discussing native PBS (“ePBS”) to reduce external relay dependence; researching encrypted mempools and delayed reveals to limit exploitable windows.

- Transaction Layer: Intent-driven trading and order flow markets are emerging—wallets and aggregators compete for best execution on behalf of users, returning part of extracted value.

- Cross-Domain Layer: The rise of L2s and rollups introduces new cross-domain MEV challenges—shared sequencing networks will need fair distribution mechanisms between chains and domains.

Key Takeaways on Miner Extractable Value (MEV)

MEV reflects economic spillovers from public transaction flows and predictable rules under ordering control: whoever influences “who goes first” has profit opportunities. Post-Merge role separation brings new governance and censorship challenges. For users: control slippage, use private channels or intent-based matching, split large trades, and avoid congestion when possible. For developers/protocols: balancing efficiency with fairness in designing defenses and value allocation will remain central for some time. Every on-chain action carries price and execution risk—users must assess their own risk tolerance carefully.

FAQ

Can MEV Front-Running Cause My Transaction to Fail?

MEV front-running can cause your transaction to fail, increase slippage, or raise costs—it does not directly steal funds. When miners/validators insert their own transaction ahead of yours, they change price conditions so your trade may be rejected or executed at a worse price. Slippage protection and limit orders help mitigate this risk.

Why Do I Often See Retry Notifications When Trading on DEXs?

This usually results from MEV dynamics. While your transaction waits in the mempool, others may front-run your order, altering pool prices so your slippage protection triggers a rejection. Increasing gas fees or using private relay services (like Flashbots) can reduce front-running chances.

Can I Avoid MEV Issues by Trading on Gate?

Trading on centralized exchanges like Gate avoids MEV because they use centralized matching engines rather than on-chain smart contracts. However, if you use Gate’s on-chain ecosystem products or transact via DeFi protocols, you must still manage MEV risks. For large on-chain trades, always weigh MEV costs and platform choice.

What Does MEV Mean for Crypto Beginners?

MEV represents a hidden cost in on-chain trading. For beginners: its impact is minimal for small trades; for large trades, choose less congested times or protective services; set slippage limits on DEXs; use centralized exchanges when needed for safety. These measures help prevent unnecessary losses.

Are MEV Issues Worse on Layer 2 Networks?

MEV issues are generally less severe on Layer 2 networks than Ethereum mainnet due to higher throughput, lower costs, and less competition. However, some Layer 2 solutions still have sequencing risks. Using Layer 2s with privacy features or waiting for more robust MEV protection tools will further improve user experience.

Related Articles

Exploring 8 Major DEX Aggregators: Engines Driving Efficiency and Liquidity in the Crypto Market

The Future of Cross-Chain Bridges: Full-Chain Interoperability Becomes Inevitable, Liquidity Bridges Will Decline