frontrunner define

What Is a Front-runner?

A front-runner is an entity that positions its transaction ahead of others before execution.

This term describes participants who, after detecting another party’s imminent trade, submit their own order to the front of the queue, altering the sequence or price to profit from the spread. On-chain, this is commonly executed by bots monitoring the mempool (the public pool of pending transactions); on centralized exchanges, it relies on faster network connections or superior API access to jump the order queue.

Typical tactics include “sandwich attacks” (buying before and selling after your trade) and liquidation front-running (executing liquidations just before a loan position is forcibly closed). These behaviors increase slippage and trading costs for regular users.

Why Does Understanding Front-runners Matter?

Front-runners have a direct impact on your transaction price and user experience.

If you swap tokens on a decentralized exchange (DEX), participate in NFT minting, or use lending protocols, front-runners can “sandwich” your transaction, causing you to pay more or receive less. On centralized exchanges, slower order routing can mean missed opportunities to faster participants.

Understanding how front-runners operate can help you set appropriate slippage limits, choose safer trading routes, and utilize protection tools to minimize unnecessary losses. For project teams, recognizing these tactics enables designing safer launch processes and reducing attack risks.

How Do Front-runners Work?

Front-running relies on observing others’ intentions and getting ahead in the queue.

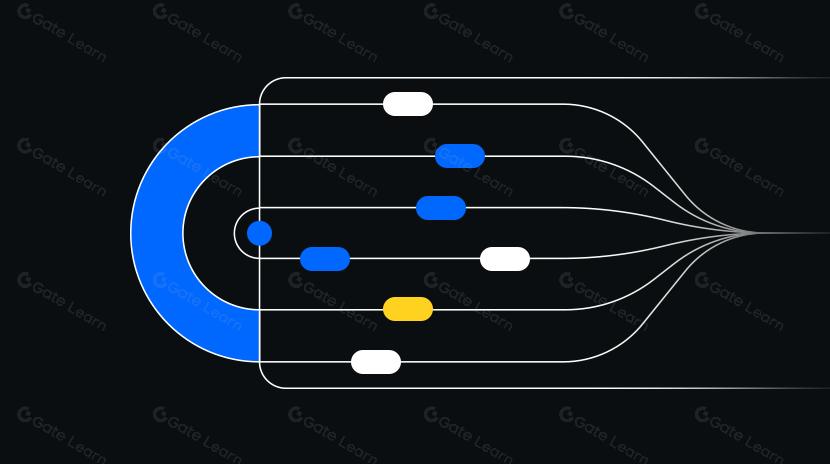

On-chain, transactions first enter the mempool, where validators pick which ones to include in a block. Front-runners use bots to monitor the mempool continuously; when they spot large swaps or imminent liquidations, they increase their gas fees (transaction priority fees) to move their trades up in the queue.

The typical “sandwich attack” follows three steps:

- The front-runner detects your plan for a large purchase in a pool and submits a small buy order ahead, slightly pushing up the price.

- Your original transaction is executed at this now higher price, increasing your actual cost.

- The front-runner immediately sells the tokens they just bought, capturing the price difference caused by your trade.

On centralized exchanges, the principle is similar but the method differs. Front-runners cannot see the exact details of pending orders but leverage faster networks, colocated servers, or superior APIs to get their orders ahead in the matching engine’s queue, allowing them to capitalize on short-term price movements.

How Do Front-runners Operate Across Crypto Markets?

Front-running takes different forms depending on the context.

On DEXs like Uniswap, sandwich attacks are common during periods of high volatility for popular tokens. Sudden price spikes or unexpected slippage are often signs of being targeted.

In NFT minting, bots may submit mass transactions with high gas fees during high-demand launches, leading to “failed but still charged” outcomes for users or increased costs due to network congestion.

In lending protocols, bots front-run liquidations to claim rewards before others. Users who fail to adjust their collateral in time are more likely to be liquidated.

On centralized exchanges—such as Gate for spot and derivatives—“queue priority” strategies are prevalent. Lower-latency traders can place limit orders at the top of the book for priority execution; during volatility, they can also rapidly cancel or adjust orders. While this isn’t identical to on-chain front-running, the impact on ordinary users’ trading experience is comparable.

How Can You Reduce Exposure to Front-runners?

Focus on minimizing intent exposure and eliminating exploitable gaps.

- Set reasonable slippage limits. Adjust your maximum acceptable slippage when swapping tokens to avoid forced execution after being sandwiched.

- Use private transaction channels. On Ethereum, wallets or routers supporting private relays can send transactions directly to block builders, avoiding exposure in public mempools.

- Split large orders. Breaking up significant swaps into smaller trades reduces immediate price impact and lowers your chance of being targeted.

- Opt for RFQ (Request For Quote) or TWAP (Time-Weighted Average Price) strategies. These execution types make it harder for adversaries to predict your full intent.

- Choose pools or time periods with higher liquidity. Deeper pools and lower volatility reduce front-running profits and thus their prevalence.

- On platforms like Gate, use appropriate order placement strategies. Maker-only limit orders can earn rebates and avoid chasing prices; during volatile periods, avoid frequent price adjustments to minimize being bumped by faster queues.

What Are Recent Trends and Key Data About Front-runners?

Over the past year, both on-chain and exchange-based “queue battles” have evolved.

On Ethereum, public dashboards and community analysis show that as of Q4 2025, blocks constructed via relays (MEV infrastructure) consistently cover around 90% of activity. High coverage means transaction ordering is increasingly handled by professional builders and has become more competitive.

For attack types, throughout 2025, sandwich-related suspicious transactions in major tokens often fluctuate between 0.5% and 2% during peak activity, with occasional spikes during market surges. These proportions depend on market volatility, pool depth, and user adoption of private channels.

On Layer 2 networks like Arbitrum, Base, and Optimism, daily transaction volumes continued rising throughout 2025. Front-running and liquidation strategies have migrated accordingly, but since block proposers control ordering—and some transactions use private routes—visible traces of front-running are relatively fewer.

On centralized exchanges, in 2025 major platforms continued optimizing APIs and matching engines. For regular users, a prudent approach is to avoid aggressive price chasing or frequent order changes—during high volatility, queue position can greatly affect execution outcomes.

Data note: The above timeframes (“past year,” “2025 overall,” “as of Q4 2025”) summarize findings from public dashboards and community analysis. Specific numbers may vary with market conditions, pool selection, and user behavior.

What Is the Difference Between Front-runners and MEV?

They are related but not identical concepts.

MEV (Maximal Extractable Value) refers to all value that can be extracted from transaction ordering in blockchains—encompassing both positive and negative actions. Positive examples include cross-pool arbitrage restoring price balance; negative cases like sandwich attacks harm regular users. A front-runner specifically describes individuals or strategies that gain priority placement—making it a typical subset of MEV tactics.

Understanding this distinction helps avoid conflating all on-chain bots with malicious behavior. You can guard against harmful forms of front-running while benefiting from improved liquidity and pricing mechanisms brought by positive MEV activity.

Related Terms

- Front-running: The act of profiting by submitting an order ahead of pending transactions based on early knowledge of those trades.

- Mempool: The space where blockchain nodes store unconfirmed transactions—a primary source of information for front-runners.

- Gas fees: Transaction fees paid on blockchains that affect transaction prioritization.

- Slippage: The difference between the expected price of a trade and its actual execution price; often worsened by front-running.

- Atomicity: The property that a transaction is either fully executed or not at all—ensuring transactional consistency.

FAQ

What does “Front Run” mean?

Front Run refers to the act of exploiting information advantages to execute similar trades just before yours gets included in a blockchain block—profiting from your market impact. In simple terms: someone gets ahead of your order to benefit from the price movement your large trade will cause. This is most common on decentralized exchanges (DEXs), where transactions reside in a public mempool before confirmation.

How do front-runners typically profit?

Front-runners primarily profit in three ways: (1) Buying before your purchase and selling after your trade pushes up prices; (2) Selling before your sale to drive prices down and then buying up your cheaper assets; (3) Monitoring large trades in transaction pools to predict market direction and pre-position accordingly. They usually pay higher gas fees so miners prioritize their transactions.

Can you encounter front-running on Gate Exchange?

Gate is a centralized exchange where matching is handled by an internal engine—meaning classic front-running does not occur here. By contrast, decentralized exchanges (like Uniswap) are more susceptible due to transaction transparency and mempool mechanics. Using Gate for spot trading can effectively avoid such risks.

How can regular traders protect themselves from front-running?

Several defensive measures can help: set slippage limits to prevent excessive price deviation; use split-order strategies to make large trades less detectable; choose centralized exchanges like Gate to avoid DEX-specific risks; or use advanced tools such as private pools when transacting on-chain.

Is front-running legal?

Legality depends on context. In traditional stock markets, front-running constitutes illegal insider trading. In crypto markets—especially DEXs—lack of centralized regulation means its legal status is ambiguous. However, most communities consider it unfair practice from an ethical and market integrity standpoint, driving technical solutions (like MEV-Burn mechanisms) aimed at combating it.

Related Articles

Exploring 8 Major DEX Aggregators: Engines Driving Efficiency and Liquidity in the Crypto Market

What Is Copy Trading And How To Use It?